Défaillance SSPA / SSPA failure

Text in English below.

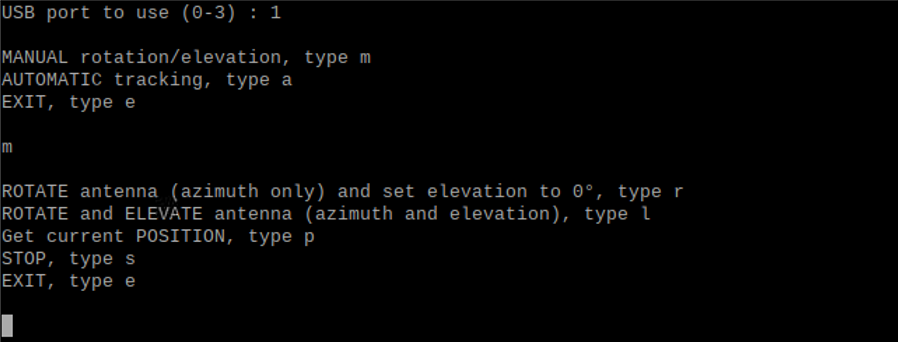

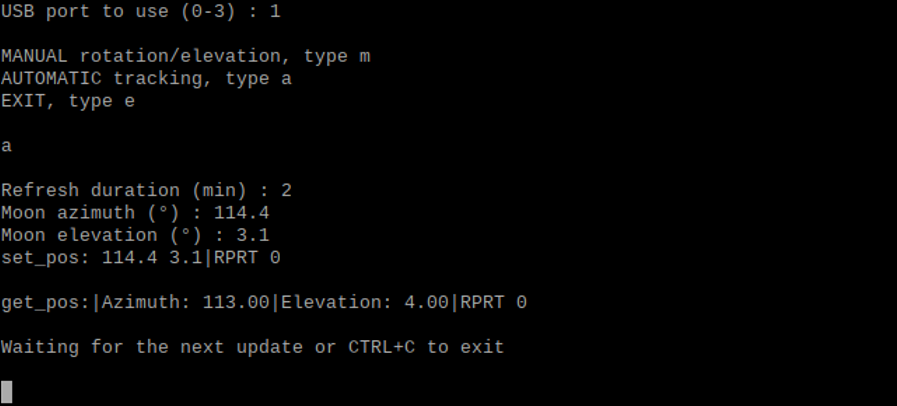

Etant donné que je suis actif sur 144 MHz en EME (terre-lune-terre), j’ai besoin de puissance RF. Après une version 300W, puis 600W, j’ai construit un SSPA (Solid State PA) de 1 kW+ en 2017 (une vidéo relative à cet ampli est disponible ici). Il est basé sur un kit de Jim, W6PQL (matériel très fiable). Le transistor utilisé est un BLF188XR. Cet ampli a parfaitement fonctionné jusque mi juin 2023. Durant une émission en mode numérique et par journée chaude (31°C), il a cessé de fonctionner ! Pour limiter les pertes, le transverter 28 <> 144 MHz et l’ampli sont disposés dans un abri au pied de mon pylône, dans le jardin. L’abri n’est pas climatisé, si bien que par les journées chaudes, le refroidisseur est déjà à 30°C+ sans avoir même émis un watt RF…

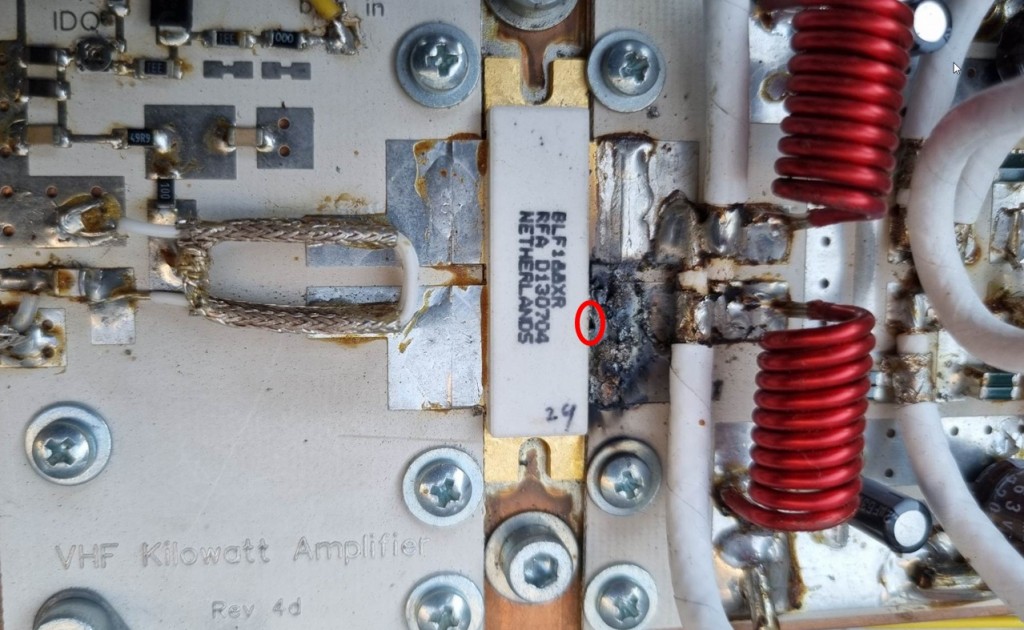

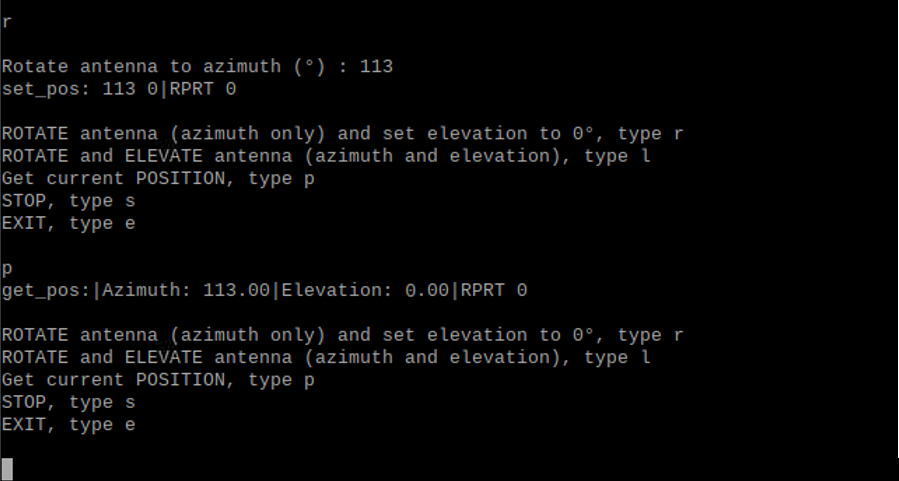

L’examen de l’ampli après sa défaillance montre une fonte partielle du drain droit et il y a un petit trou dans le drain, juste à la base du boîtier du transistor (voir photo). La vérification à l’ohm-mètre indique que le drain droit n’est plus en contact avec le PCB. A ce moment-là, je me dis qu’il faudra remplacer le transistor, ce qui ne me ravit pas. Un transistor neuf coûte 250€ et l’opération de dessoudage et ressoudage du transistor sur la semelle en cuivre n’est pas une opération aisée !

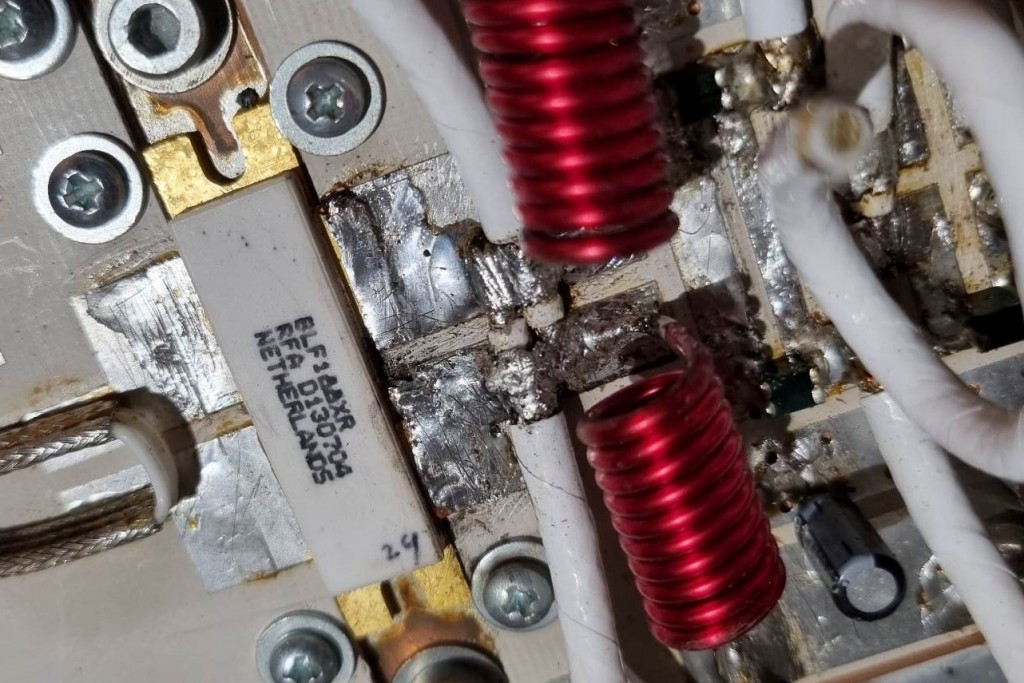

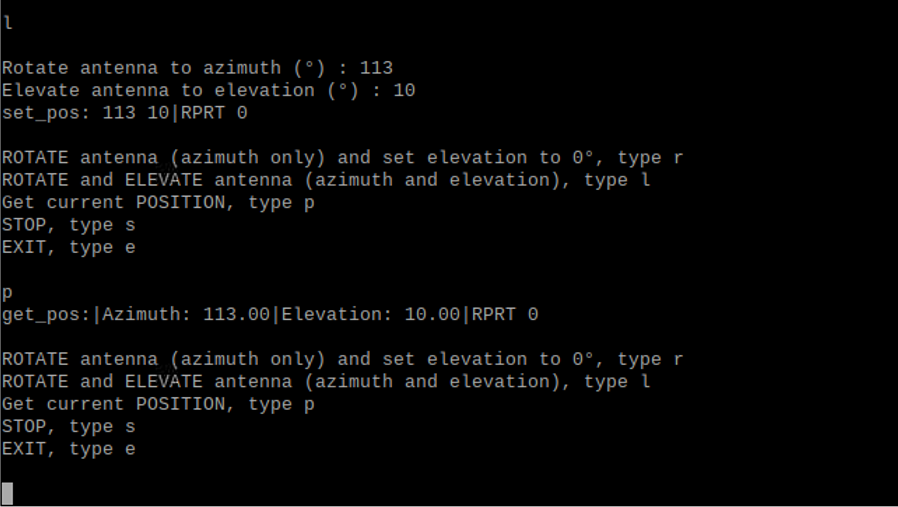

Sans trop y croire donc, j’ai essayé de récupérer autant que possible le drain fondu. Cette opération de “récupération” passait par le retrait (même partiel) de la forte oxydation du drain liée à la fonte. J’ai ensuite refait une soudure sommaire, juste pour rétablir le contact entre le drain défaillant et le PCB. Ensuite, j’ai mesuré à l’ohm-mètre la résistance entre les gates du transistor (l’ohm-mètre ne doit pas envoyer plus de 3-4 V) et la source du transistor qui se trouve à la masse (soudée sur le refroidisseur). Ce, en ayant pris soin de dessouder les composants périphériques qui mettent en contact direct (DC) les gates à la masse. La mesure indique une résistance infinie. C’est bon signe, les gates ne sont pas en court-circuit. Idem pour les drains (mesure de la résistance drains – masse) et la résitance est de l’ordre du mégohm (de mémoire), ce qui est également bon signe. Le transistor ne serait-il pas claqué ? Manipulation suivante (après ressoudage des composants périphériques) : mise des drains sous tension nominale (52V) et application de la tension de polarisation sur les gates (environ 2V). Le courant (de repos) dans les drains indique 3A, ce qui est également bon signe. J’ai donc fait une soudure plus sérieuse du drain droit (avec application d’un feuillard en cuivre, voir photo) et renforcé quelques autres soudures. A l’application d’une puissance RF en entrée, et après avoir réaligné le courant de repos à 2A, l’ampli sort à nouveau près de 1,2 kW. Contre toute attente, le transistor n’était donc pas claqué !

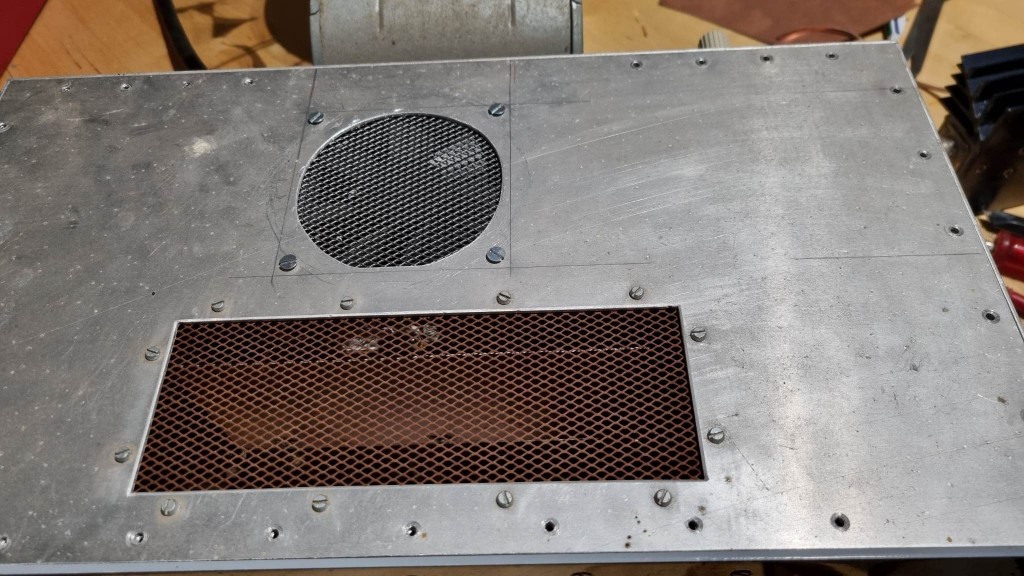

J’attribue la défaillance, soit à une dégradation graduelle de la soudure des drains en raison de la température (dissipation thermique), jusqu’à rupture et arc électrique, ou à la présence d’un insecte dans l’ampli (pour rappel, il est dans le jardin) qui aurait amorcé un arc électrique. Pour rendre durable la réparation, j’ai revu un peu la gestion du refroidissement. En plus de la ventilation forcée déjà en place sur le refroidisseur, j’ai mis un ventilateur au-dessus de PCB, pour le refroidir et dissuader la présence d’un insecte. Sur la carte de contrôle de W6PQL (V6), j’ai appliqué 3,2V (au lieu de 2,8V) sur le “test point 1”, afin de diminuer le seuil d’enclenchement/maintien de la ventilation forcée (ventilateurs).

Since I’m active on 144 MHz in EME (earth-moon-earth), I need RF power. After a 300W, then a 600W version, I built a 1kW+ SSPA (Solid State PA) in 2017 (a video relating to this amp is available here). It’s based on a kit from Jim, W6PQL (very reliable equipment). The transistor used is a BLF188XR. This amp worked perfectly until mid-June 2023. During a digital transmission on a hot day (31°C), it stopped working! To limit losses, the 28 <> 144 MHz transverter and the amplifier are placed in a shelter at the foot of my tower, in the garden. The shelter is not air-conditioned, so on hot days the heatsink is already at 30°C+ without having emitted even one RF watt…

Examination of the amp after its failure shows partial melting of the right drain and there’s a small hole in the drain, just at the base of the transistor case (see photo). A check with the ohm-meter shows that the right drain is no longer in contact with the PCB. At this point, I say to myself that I’m going to have to replace the transistor, which I’m not happy about. A new transistor costs 250€ and unsoldering and re-soldering the transistor to the copper plate is not an easy operation!

Without really believing in it, I tried to recover as much of the melted drain as possible. This “recovery” operation involved removing (even partially) the heavy oxidation from the drain due to melting. I then did some rough soldering, just to re-establish contact between the faulty drain and the PCB. Then I used an ohm-meter to measure the resistance between the gates of the transistor (the ohm-meter shouldn’t send more than 3-4 V) and the source of the transistor, which is at earth (soldered onto the heatsink). I took care to desolder the peripheral components that put the gates in direct contact (DC) with earth. The measurement indicates infinite resistance. This is a good sign that the gates are not short-circuited. The same goes for the drains (measurement of the resistance drains – earth) and the resistance is of the order of one megohm (from memory), which is also a good sign. Could the transistor still be working? Next step (after re-soldering the peripheral components): apply nominal voltage (52V) to the drains and apply the bias voltage to the gates (about 2V). The (quiescent) current in the drains indicates 3A, which is also a good sign. So I did a more serious soldering of the right drain (with application of a copper strip, see photo) and reinforced a few other solder joints. When RF power was applied to the input, and after realigning the quiescent current to 2A, the amp once again produced almost 1.2 kW. So, against all expectations, the transistor wasn’t blown!

I attribute the failure either to a gradual degradation of the soldering of the drains due to the temperature (heat dissipation), until it broke and arced, or to the presence of an insect in the amp (as a reminder, it’s in the garden) which initiated an electric arc. To make the repair sustainable, I’ve reviewed the cooling management a little. In addition to the forced ventilation already in place on the heatsink, I put a fan on top of the PCB, to cool it and dissuade the presence of an insect. On the W6PQL control board (V6), I applied 3.2V (instead of 2.8V) to “test point 1”, in order to lower the threshold for switching on/holding the forced ventilation (fans).

SPACE